Disagreeing Well: Structure a Debate That Builds, Not Breaks

Preparation, awareness of logical fallacies, and civil discourse are essential for achieving a win-win debate outcome. Without these elements, a debate is unlikely to lead to productive outcomes.

Two recently published statements echo this sentiment:

“In disagreements, civility is not a luxury. It’s a necessity. Disrespect provokes defensiveness and prevents critical thinking. Respect prompts openness and promotes logical reasoning. The ability to debate without disdain is a foundation of intelligence.”

—Adam Grant

“Logical fallacies are flawed arguments that sound convincing, but don’t hold up. [People] use them to distract, manipulate, or win—not to get to the truth… The goal of a real debate isn’t to ‘win’—it’s to understand each other and move forward together. But too often, we argue to feel morally superior.”

—Stephanie Berenice

Making Your Case: Prepare for the Debate

Define Your Audience: Consider the motivations, beliefs, and position of the person you’re debating, as well as the listeners of your debate. By appealing to their motivations, you may be able to persuade them of your argument more effectively.

Define Your Debate Scope Narrowly: Commit to a single topic supported by contentions (usually three), and outline them in a compelling opening statement. A narrow debate focus will help prevent you from becoming distracted by an opponent’s ‘red herring’ tactic to take the argument off-track. It will also make it easier for your audience to follow along with your argument.

Support Your Argument with Research: Use concrete examples, statistics, and fact-based research to defend your argument and tell your audience a compelling story clearly to convince them of the benefits of your position.

Anticipate the Counter-Argument: Research your audience’s potential biases and prevailing arguments ahead of the debate. Remember, popular opinion or tradition doesn’t mean the status quo is the optimal solution. Recognize that your audience, including your opponent, may fall for confirmation bias–they seek out and interpret information that proves their beliefs.

Identify the Weak Points of Your Argument: By considering the potential flaws in your argument, you’ll be better positioned to counter a well-researched opponent. By proactively acknowledging a weak point and providing solutions, you can still convey the strength of your argument by the fact that you still support it, despite potential flaws.

During the Debate: Refuting Your Opponent’s Case

Dialogue in a Civil Manner: Ask questions, take notes to remember the details, and answer questions directly and respectfully, choosing the tone that best suits your argument. Don’t be afraid to rephrase a question, but try to limit the times you do this in a single debate. Remember that you are refuting your opponent’s ideas - not your actual opponent.

Stay on the Offensive: Because you’ve researched your opponent’s position, identified the potential arguments, and evaluated your opponent’s possible motivations, you’ll be better prepared to re-direct or counter an argument. If you are playing defense the entire debate, there is a good chance you will have strayed from your narrowly focused argument.

Admit Mistakes Early: If you make a mistake during the debate, acknowledge and address it promptly.

Deliver a Memorable Closing Statement: Summarize the main points of your argument, refutate your opponent’s case clearly if necessary, highlight key evidence to support your case, and end with a call to action for your audience.

Post Debate

Control the narrative of your debate while it is still fresh in your mind and your audience’s mind. Publish an article (or submit a press release to the media), post a presentation summarizing your case, or speak in a public forum (i.e., on a podcast or with the press). Make sure your content is easily discoverable in the public domain, preferably on your brand’s website and official social media accounts.

Conclusion

Researching your case and its counterarguments, as well as identifying your audience (i.e., the opponent and those witnessing your debate), are crucial to crafting a compelling, persuasive argument. Dialoguing civilly and asking your opponent questions should encourage them to respond in kind. Offensive posturing to proactively recognize–and not react instinctually to–cognitive fallacies in your opponent’s argument will also help you keep you focused on your argument and manage the debate more effectively.

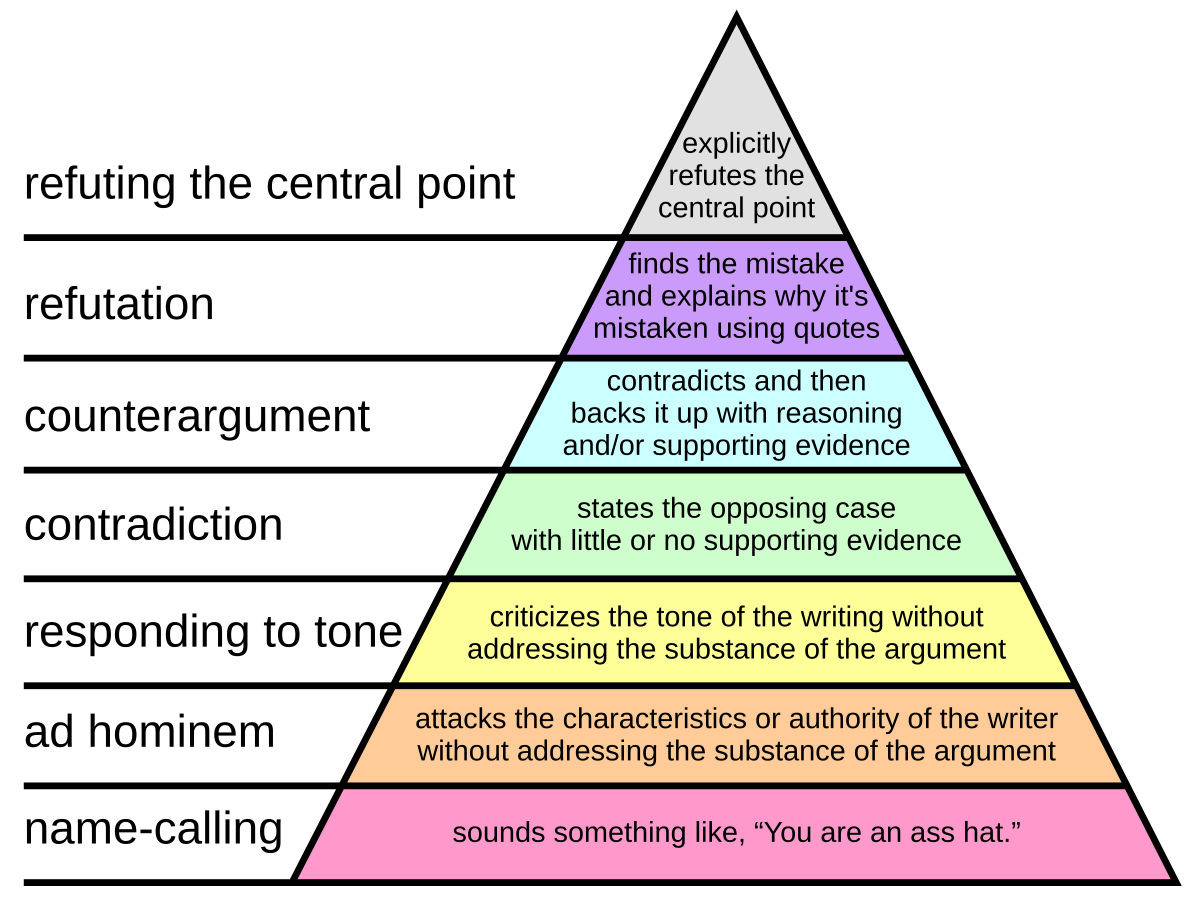

Paul Graham’s “How to Disagree”

The "hierarchy of disagreement" from the essay "How to Disagree" by Paul Graham.

“The most obvious advantage of classifying the forms of disagreement is that it will help people to evaluate what they read. In particular, it will [allow] them to see through intellectually dishonest arguments.

“An eloquent speaker or writer can give the impression of vanquishing an opponent merely by using forceful words. In fact, that is probably the defining quality of a demagogue.

“By giving names to the different forms of disagreement, we [provide] critical readers a pin for popping such balloons.

“But the greatest benefit of disagreeing well is not just that it will make conversations better, but that it will make the people who have them happier.

“If you study conversations, you find there is a lot more meanness down in [Ad Hominem] than up in [Refuting the Central Point].

“If you have something real to say, being mean just gets in the way. If moving up the disagreement hierarchy makes people less mean, that will make most of them happier. Most people don't really enjoy being mean; they do it because they can't help it.”

Labor Day marks the unofficial end of summer, symbolized by backyard barbecues and beach trips. Beyond the holiday sales and seasonal farewells on the beach, the federal holiday holds a deeper significance: it serves as a day to honor the invaluable contributions and rights of American workers.